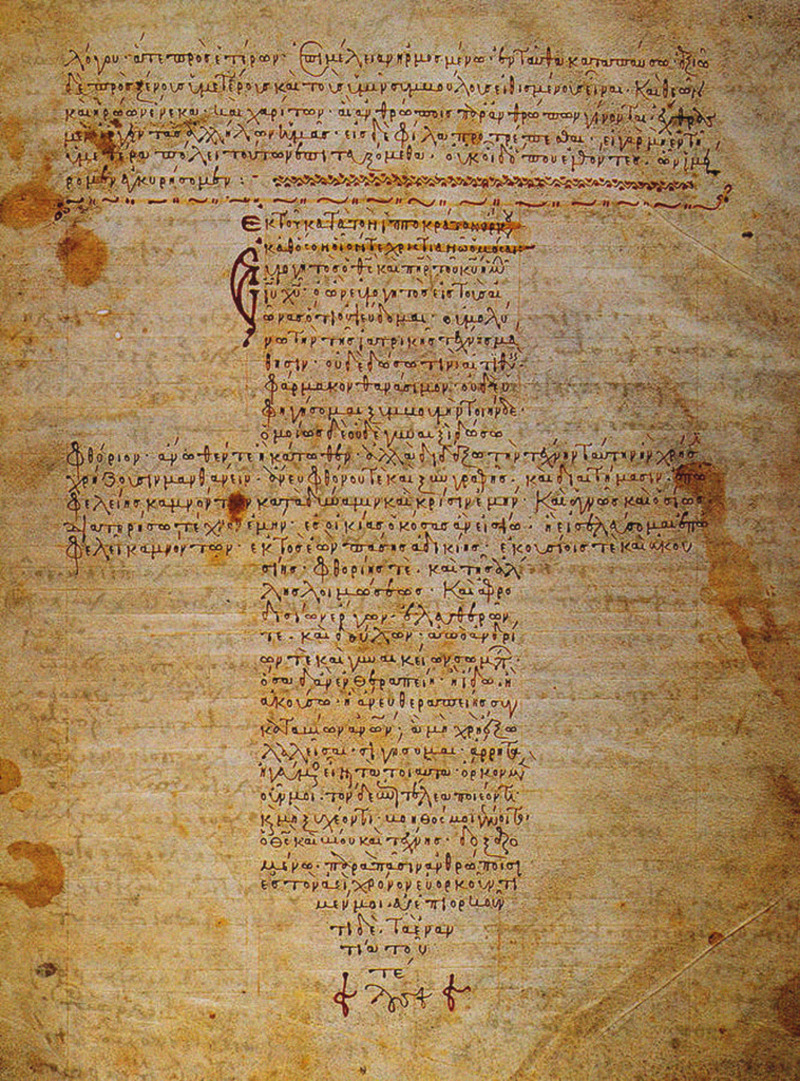

Doctors in Ancient Greece wrote recipes to cure their patients’ ailments and even determine the sex of their children. Hippocratic doctors used to say that Greek women’s wombs could be displaced at any moment, and it could move around various sections of their bodies to the point of potentially strangling them. This was documented in medical notes discovered in the 5th century B.C. and traced back to Hippocrates as well as his followers. It influenced Greek science through their findings that rather than divine causes alone, illnesses were more of a result of natural causes. Although the “wandering womb” syndrome has been widely determined to be false (thank goodness), modern parents can relate to the Hippocratic notion that one’s diet may determine a child’s sex.

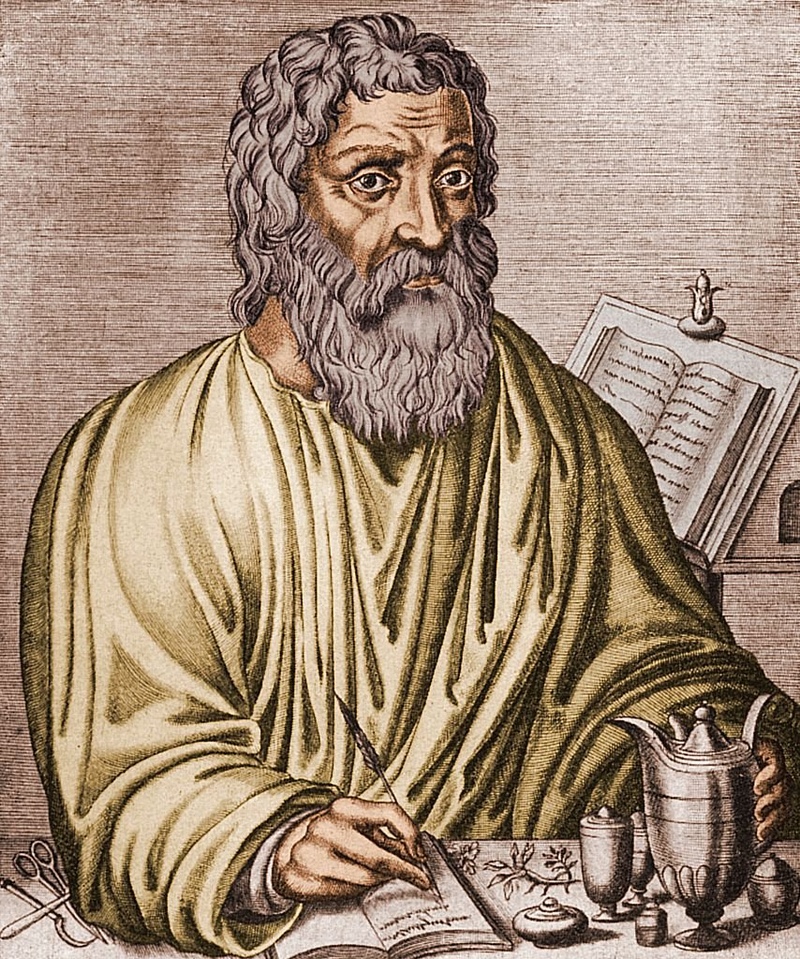

There may be little data regarding Hippocrates’ life in the texts found, but the Hippocratic corpus was popular for centuries, it was even filed in the Great Library of Alexandria. Many of its thousands of recipes were brought forth from gynecological treatises, suggesting that their ancient doctors were highly concerned about the reproductive health of their women. It prescribed specific diets to be followed in order to choose the sex of one’s child. Ancient Greek doctors pointed out that 3 or 4 humors ruled the body, and they were categorized according to its moisture and heat: phlegm (cold/wet), blood (hot/wet), black and yellow bile (hot, cold or dry dependent on texture). It is said that this comprehensive system covered a patient’s overall health aspects. And based on Hippocratic doctors’ medical concepts, to determine a food’s classification, they considered how they thought it interacted with the body’s humors. For example, they believed red wine heated and made the body parched. Meanwhile, they said white wine moistened and cooled the body.

In Hippocratic medicine, it was vital for women to balance body humors when trying to conceive. In those times, infant mortality was high, therefore, proper care had to be followed. Children benefited families in many ways. Boys meant potential political power and economic stability, while girls foretasted the possibility of alliances of strong families through marriage. It has long been presumed that boys were more valuable to the Greeks, but there is also evidence of women praying to the Gods to bless them with daughters.

Due to the medical texts, Greeks had adopted a more scientific approach to matters. Their doctors believed that conception was an outcome of a battle between a man’s strong seed and a female’s weak seed. The determination of a child’s sex was dependent upon which seed survived the fight. Parents who sought doctor’s help were told to consume more foods that are dry, hot, and strong if they wanted to work on having a baby boy. Those who wanted a girl were advised to take feminine foods (wet, cool) like white wine and lettuce. Diet was just one of their prescriptions. For those who wanted to take a more serious approach that wasn’t sufficient enough. Since they believed that female infants were nurtured on the left side of the womb and, conversely, the right area nurtured males, they concluded that couples had to conceive on the corresponding side in relation to their desired gender. So oddly, they advised couples who wanted a girl, that the male partner’s right testicle had to be tied with a string to effectively shoot sperm to the womb’s left side.

Most of the content of the medical texts is no longer relevant today, but things such as the Hippocratic oath, which pledges that doctors should do no harm still stand today. Dr. Rebecca Fallas, a researcher at the UK Open University, says that it’s hard to tell if the practice of following prescription diets directly comes from Hippocratic medicine or some folklore, but doctors say this advice is baseless. Obviously, eating vegetables doesn’t necessarily result in conceiving girls, and Fallas believes this practice is rooted in the woman’s predilection to control her health within the confines of her own homes by making use of what was already present. Fallas adds, with it, “You’ve got a 50/50 chance of getting it right.”