Scientists are still baffled by how ancient humans acquired the ability to process visual information. In a world where reading and writing didn’t exist, how could our ancestors develop this kind of skill? Researchers say that to understand the transition, they should uncover how and why humans started to make repetitive marks first.

Conducting extensive visual cortex brain imaging, done on individuals while reading text, produced great insights into how our brain processes specific patterns. A recently published paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports analyzed the earliest human-made patterns. Their purpose appeared to be more aesthetic than symbolic.

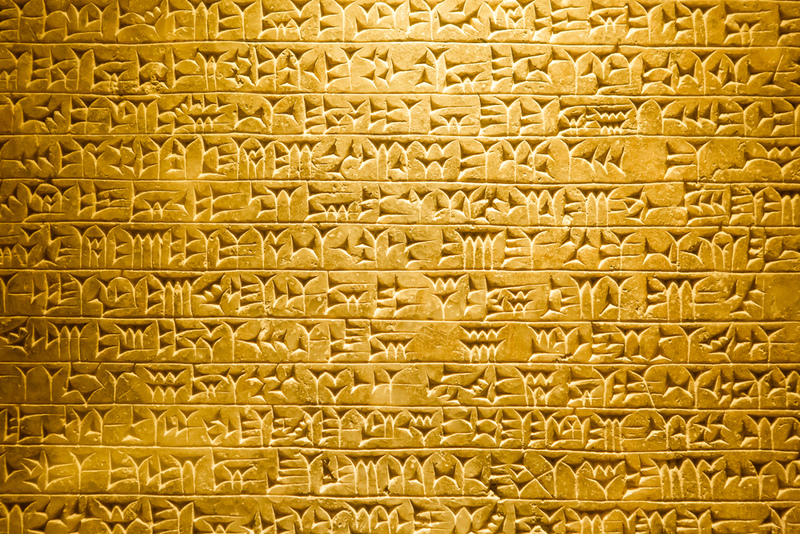

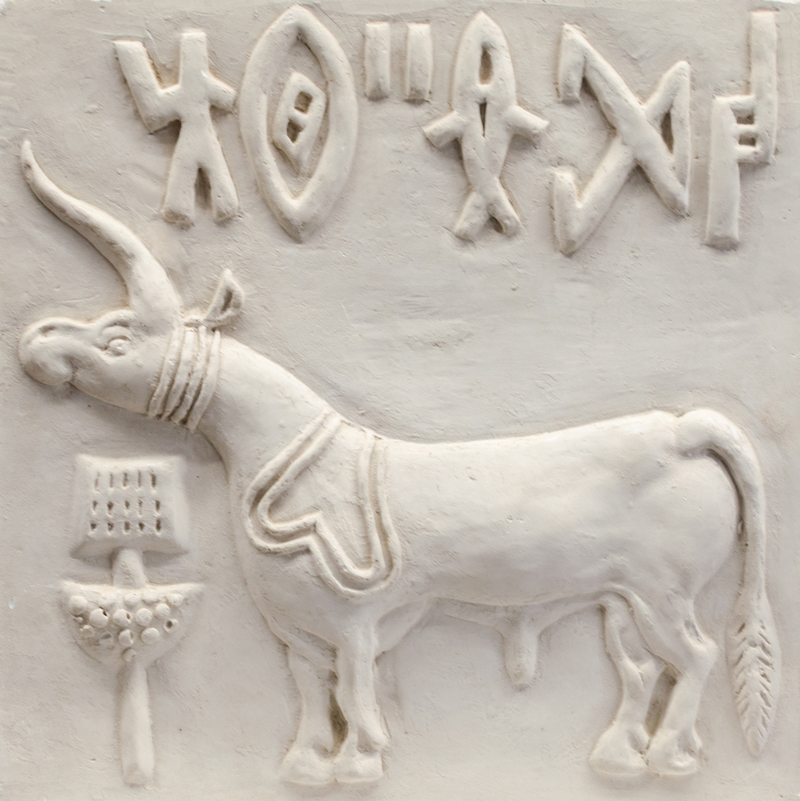

Discoveries of ancient patterns engraved by early humans, Neanderthals, and Homo Erectus that date back to 100,000 years ago, continue to increase in number. Archaeologists retrieved these artifacts from South Africa, where they also found one shell engraving made by a Homo Erectus that dates back 540,000 years. Almost all of these engraved symbols featured angles, grids, and repetitive lines.

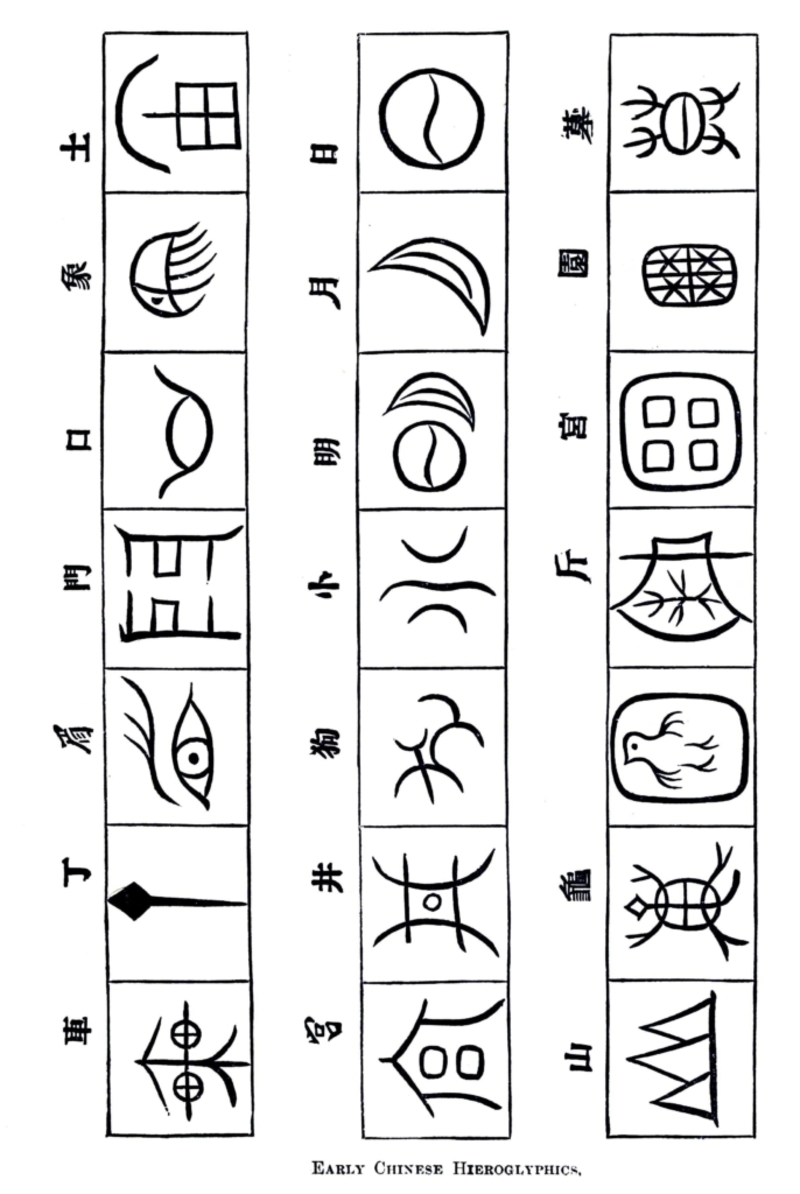

Researchers suggest that the early visual cortex, where the information gathered by the eye first impacts the brain, is the reason behind our ability to understand and create simple patterns. Angles, intersections, and lines are abundant in the natural environment; these can serve as critical first cues on how to layout objects.

Primates share our ability to process images, but we respond to these cues through the “Gestalt Principles,” a set of rules that enable our minds to understand patterns in an instant. 700,000 years ago, our sensitivity to patterns and geometry enabled our species to start creating “Acheulean Tools,” which exhibit different angles and patterns. Creating these tools helped our ancestors develop sensitivity to patterns that occur in the natural environment. They started noticing that markings can be made on shells, rocks, and ochre.

As they continued to notice accidental patterns, they learned that they could use these materials to engrave designs that would, later on, evolve into writing. Neuro-scientific research reveals that writing involves the brain’s premotor cortex, a part of the brain that drives manual skills.

Since our ancestors wrote abstract patterns, it helped them activate the “mirror neurons” in their brains. These cells help us identify the actions of others and relate them to ourselves. It also produces a sense of pattern identification and the ability to replicate it. These advancements developed and gave an entirely new purpose to the visual cortex of our brain. It might have provided a way for the brain to have the ability to connect with speech visually and vice versa. Scientists argue whether these early marks were aesthetic or symbolic. But since a study shows that early stages of visual cortex development recognized only basic configurations, it’s most likely it was for aesthetic purposes. The oldest patterns or markings ever discovered are believed to have been created by the Homo erectus, which existed from about 1.8 million to 500,000 years ago.